Acts 20:26 Therefore I testify to you this day that I am innocent of the blood of all, 27 for I did not shrink from declaring to you the whole counsel of God. 28 Pay careful attention to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers (episkopos = a superintendent, an overseer, a bishop), to care for the church of God, which he obtained with his own blood. 29 I know that after my departure fierce wolves will come in among you, not sparing the flock; 30 and from among your own selves will arise men speaking twisted things, to draw away the disciples after them.

Continuing on with seeking to answer our question about the true church of Jesus Christ, “who is right about what is right?” We look back once again to our father, John Wesley, who was an ordained clergyman rooted in the Anglican tradition until the day of his death.

He believed it the be the best church in all of Christendom.

“What is Methodism? What does this new word mean? Is it not a new religion? This is a very common, nay, almost an universal supposition. But nothing can be more remote from the truth. It is a mistake all over. Methodism, so called, is the old religion, the religion of the Bible, the religion of the primitive church, the religion of the Church of England.” (Sermon 132 - On Laying the Foundation of the New Chapel)

That leads us to the next piece of the puzzle, from where does the church of England derive its authenticity? What are it’s own origins? Here I will quote at length from Wikipedia’s entry on the subject:

Many of the early Church Fathers wrote of the presence of Christianity in Roman Britain, with Tertullian stating "those parts of Britain into which the Roman arms had never penetrated were become subject to Christ". Saint Alban, who was executed in AD 209, is the first Christian martyr in the British Isles. For this reason he is venerated as the British protomartyr. The historian Heinrich Zimmer writes that "Just as Britain was a part of the Roman Empire, so the British Church formed (during the fourth century) a branch of the Catholic Church of the West; and during the whole of that century, from the Council of Arles (316) onward, took part in all proceedings concerning the Church."

After Roman troops withdrew from Britain, the "absence of Roman military and governmental influence and overall decline of Roman imperial political power enabled Britain and the surrounding isles to develop distinctively from the rest of the West. A new culture emerged around the Irish Sea among the Celtic peoples with Celtic Christianity at its core. What resulted was a form of Christianity distinct from Rome in many traditions and practices."

The historian Charles Thomas, in addition to the Celticist Heinrich Zimmer, writes that the distinction between sub-Roman and post-Roman Insular Christianity, also known as Celtic Christianity, began to become apparent around AD 475, with the Celtic churches allowing married clergy, observing Lent and Easter according to their own calendar, and having a different tonsure; moreover, like the Eastern Orthodox and the Oriental Orthodox churches, the Celtic churches operated independently of the Pope's authority, as a result of their isolated development in the British Isles.

In what is known as the Gregorian mission, Pope Gregory I sent Augustine of Canterbury (the first Archbishop of Canterbury) to the British Isles in AD 596, with the purpose of evangelising the pagans there (who were largely Anglo-Saxons), as well as to reconcile the Celtic churches in the British Isles to the See of Rome. In Kent, Augustine persuaded the Anglo-Saxon king "Æthelberht and his people to accept Christianity". Augustine, on two occasions, "met in conference with members of the Celtic episcopacy, but no understanding was reached between them".

Eventually, the "Christian Church of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria convened the Synod of Whitby in 663/664 to decide whether to follow Celtic or Roman usages". This meeting, with King Oswiu as the final decision maker, "led to the acceptance of Roman usage elsewhere in England and brought the English Church into close contact with the Continent". As a result of assuming Roman usages, the Celtic Church surrendered its independence, and, from this point on, the Church in England "was no longer purely Celtic, but became Anglo-Roman-Celtic". The theologian Christopher L. Webber writes that "Although "the Roman form of Christianity became the dominant influence in Britain as in all of western Europe, Anglican Christianity has continued to have a distinctive quality because of its Celtic heritage."

The Church in England remained united with Rome until the English Parliament, though the Act of Supremacy (1534) declared King Henry VIII to be the Supreme Head of the Church of England to fulfill the "English desire to be independent from continental Europe religiously and politically." As the change was mostly political, done in order to allow for the annulment of Henry VIII's marriage, the English Church under Henry VIII continued to maintain Roman Catholic doctrines and liturgical celebrations of the sacraments despite its separation from Rome. With little exception, Henry VIII allowed no changes during his lifetime. Under King Edward VI (1547–1553), however, the church in England first began to undergo what is known as the English Reformation, in the course of which it acquired a number of characteristics that would subsequently become recognised as constituting its distinctive "Anglican" identity.1

As the new nation of the United States of America, in it’s infancy stage was expanding and forming, Wesley commissioned Methodist preachers to evangelize and form Methodist Communities wherever they could. Here is a snapshot of what that growth looked like:

In 1796 the first 6 annual conferences of the Methodist Church were defined

The general minutes record a membership of 64,894 in 1800

By 1850 the figure was 1,259,906 (a growth rate of 1,939%)

During the same half century the general population increased from 5,308,000 to 23,192,00 (a growth rate of only 437% comparatively) 2

Since the preachers Wesley appointed were not ordained by the Church of England, they were not allowed to baptize new converts or serve communion. Only those properly ordained in an episcopal connection, not appointed, were allowed to provide the sacraments of the church.

Wesley attempted to seek ordinations for his preachers from the Bishop of London, but he was refused. Here is what Wesley writes in regards to one of those attempts on behalf of one of his preachers, John Hoskins:

“He [Mr. Hoskins] asked the favour of your Lordship to ordain him that he might minister to a little flock in America. But your Lordship did not see good to ordain him; but your Lordship did see good to ordain and send into America other persons who knew something of Greek and Latin, but who knew no more of saving souls than of catching whales.”3

Here is how Frederick Norwood describes Wesley’s response to the conundrum of American Methodism:

“Wesley had already thought out the historical, theological, and ecclesiastical issues and now was confronted with the argument of necessity. He had to do something about the provision of the sacraments for American Methodists . . . .

Hence, he now acted in accordance with his understanding of his position as an ordained minister of the Church of England and as the superintendent of the People Called Methodists. This position, in his view, coincided with the position of the bishops of the primitive early Fathers. A bishop, he concluded, was a presbyter who exercised authority over a diocese or segment of the church . . . He was a presbyter in apostolic succession. He was also an administrator of a large movement. This made him a “scriptural episcopos”.”4

I am now firmly attached to the Church of England as I ever was since you knew me. But meantime I know myself to be as real a Christian bishop as the Archbishop of Canterbury. Yet I was always resolved, and am so still, never to act as such except in cases of necessity.5

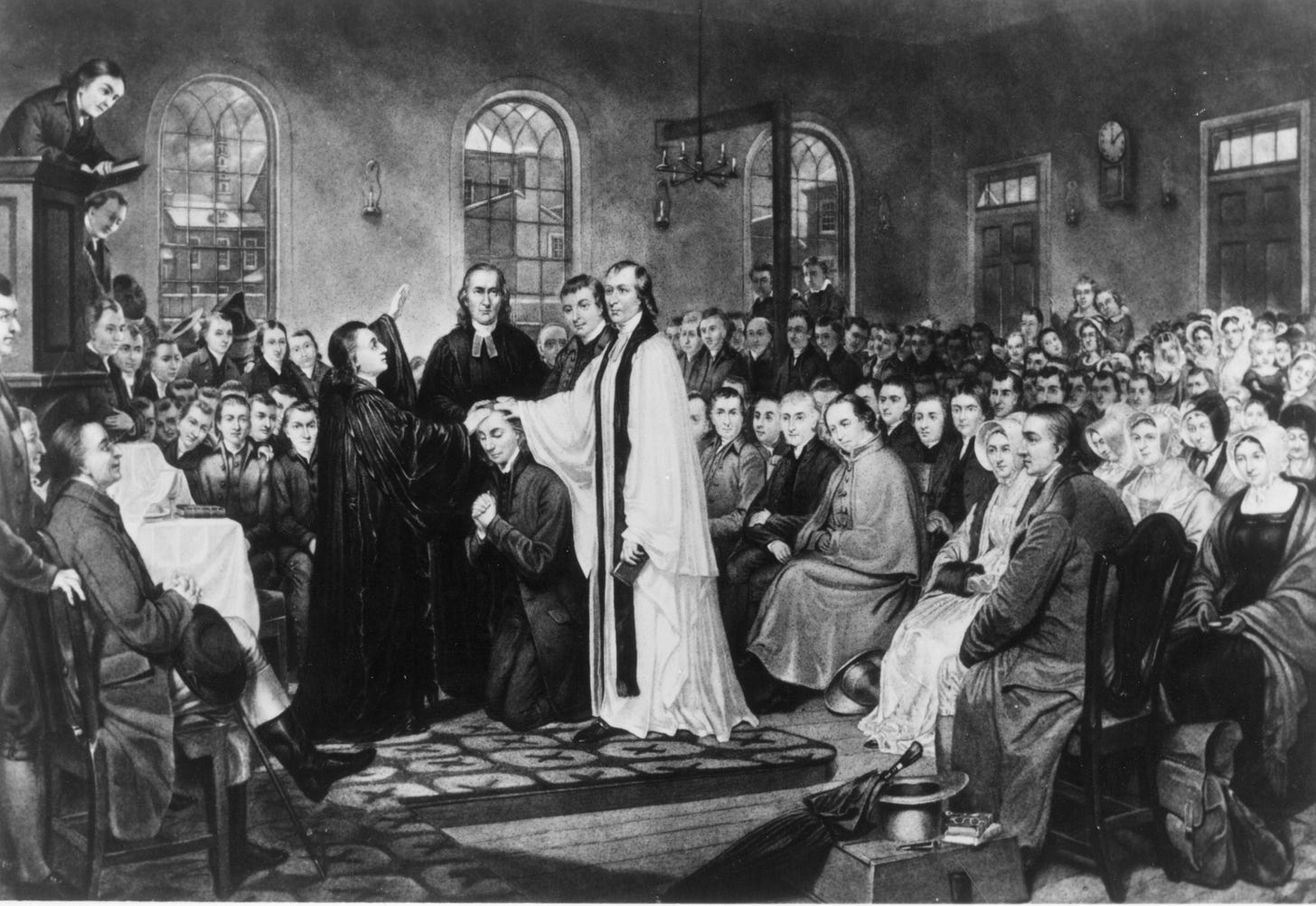

With the American Revolution decided for independence, Wesley perceived that necessity to have come. In September 1784 Wesley consecrated fellow Anglican clergyman Thomas Coke as Superintendent to the United States, a title replaced in 1787 by that of Bishop. Wesley's action took place two months before the consecration of Samuel Seabury as bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the USA.6

“Thomas Coke joined John Wesley, who found in him a valued legal mind, a gifted evangelical preacher, a skilled administrator, and in later years, his most trusted companion. After serving as superintendent of Methodism’s London circuit (1780) and first chairman of the Irish Conference (1782), Coke was ordained and appointed by Wesley in 1784 as superintendent for the work in the newly independent United States.

Coke convened the organizing conference for American Methodism at Baltimore, Maryland, in 1784 and, with authorization from Wesley, ordained Francis Asbury and consecrated him joint superintendent.”7

“But what, exactly, are we to understand Wesley to mean in his "ordaining' of Coke, already a priest, to the "Superintendency." According to Bishop Mathews, by ordaining we should understand the traditional meaning of "setting apart," and in the case of the superintendency, the Setting apart' of a presbyter for a higher functional office.

Wesley had fulfilled that office for England and America and had delegated it to Coke for America only, an office essentially episcopal in nature.”8

And that is the story of how Methodism became a uniquely American expression of the Episcopal Church of Jesus Christ in history. It is an episcopacy that is uniquely “catholic” or universal in that African Methodists are overseen by African Bishops, the Philippine Methodists by Philippino Bishops, etc. No territory is subject to British or any other singular centralized authority. We have no “popes” or “archbishops”. Only one sovereign ruler, God, and King who alone wields infallible authority over his church through the mysterious administrations of the Holy Spirit using the clumsy obedience of fallen and sinful, but called and sanctified men.

Which will lead us to our next topic, what is ordination and what is the priesthood of all believers?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglicanism

Norwood, Frederick (The Story of American Methodism) c. 1974, p. 154

Wesley, Letters, 7:31.

Norwood, p. 96

https://www.revneal.org/Writings/Writings/methepisc.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Seabury

https://www.bu.edu/missiology/missionary-biography/c-d/coke-thomas-1747-1814/#:~:text=After%20serving%20as%20superintendent%20of,the%20newly%20independent%20United%20States.

https://www.revneal.org/Writings/Writings/methepisc.htm